- Patrice Lamarque

- July 14, 2016

How to Write a Good Functional Specification

Functional specifications are an essential step in building quality software that you’ll want to support over the long term. They define the requirements to be implemented in the software.

A good specification needs to carefully describe how the software will look and behave in all situations. Here’s some battle-tested advice for writing functional specifications that will work beautifully.

Content

1. Make it a collaborative contract

In a software production organization, the functional specifications play the role of a written contract between the key stakeholders that collaborate in the making of the software. Here’s a list of what goes into making good specifications:

- Product managers should ensure that all requirements are captured and all business rules are accurate.

- Designers should define the user interface and interactions.

- QA should be able to find enough information in the document to reflect the changes in tests.

- Developers should find sufficient explanation to help them define technical specifications or directly code the corresponding features.

- Technical writers should find answers to help them write meaningful user manuals and technical documentation.

- Support teams should have a reference for qualifying customer reports as defects or normal behavior.

The specifications should be the trusted source for all teams to find answers about what the software is supposed to do.

2. Make it a living document

A specification is a living document that gets updated over the whole software lifecycle. While it can and should usually be started ahead of development, abandoning it along the way would be an unrecoverable mistake. But why would a lengthy text document be of any use when you have working software and good tests? Well, if you’re doing throwaway software such as a proof of concept, don’t spend too much time on your specification. But if you’re going to have several generations of developers writing and maintaining code for thousands of customers over many years, you’ll need a safety net when things go wrong. And your specification, if well written and up to date, will be that low-tech thing that you’ll be happy to have there to save the day.

tools and information

3. What format to use?

Many popular specification formats exist. For example, user stories (“As XXX I can do YYY so that YYY”) work well for low-touch developments and agile practices. And use cases (“Step 1, then step 2…”) are very efficient for aligning with user expectations.

But which one is the best? There’s no silver bullet, and the general advice is to pick the one that matches the best with your organization and development practices. The truth is that everybody ends up with their own format.

At eXo, we have experimented with different things over the years and have converged to a preferred format that we find quite comfortable to work with.

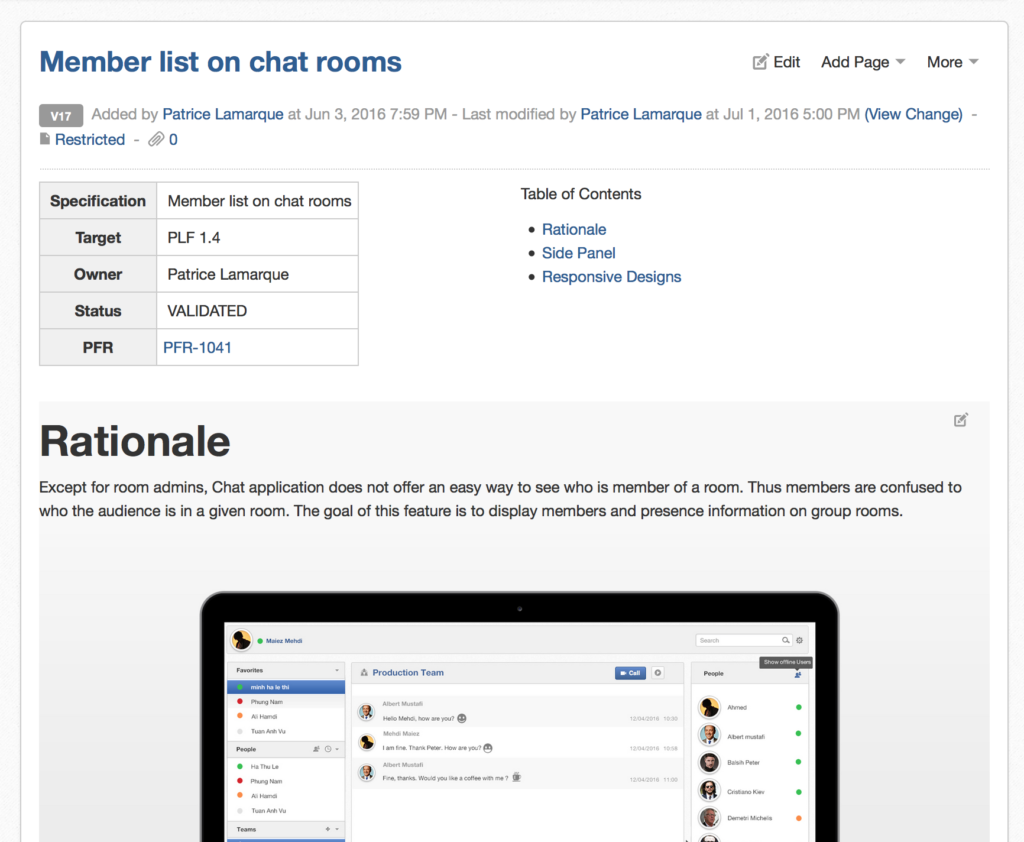

Each specification is written on a wiki page, starting with:

- a table that defines key information for the specification, such as title, description, name of the spec leader, target version, links to other resources, etc.; and

- a rationale paragraph that briefly describes why this feature is needed—because you always Start with Why, right?

Streamline internal communications

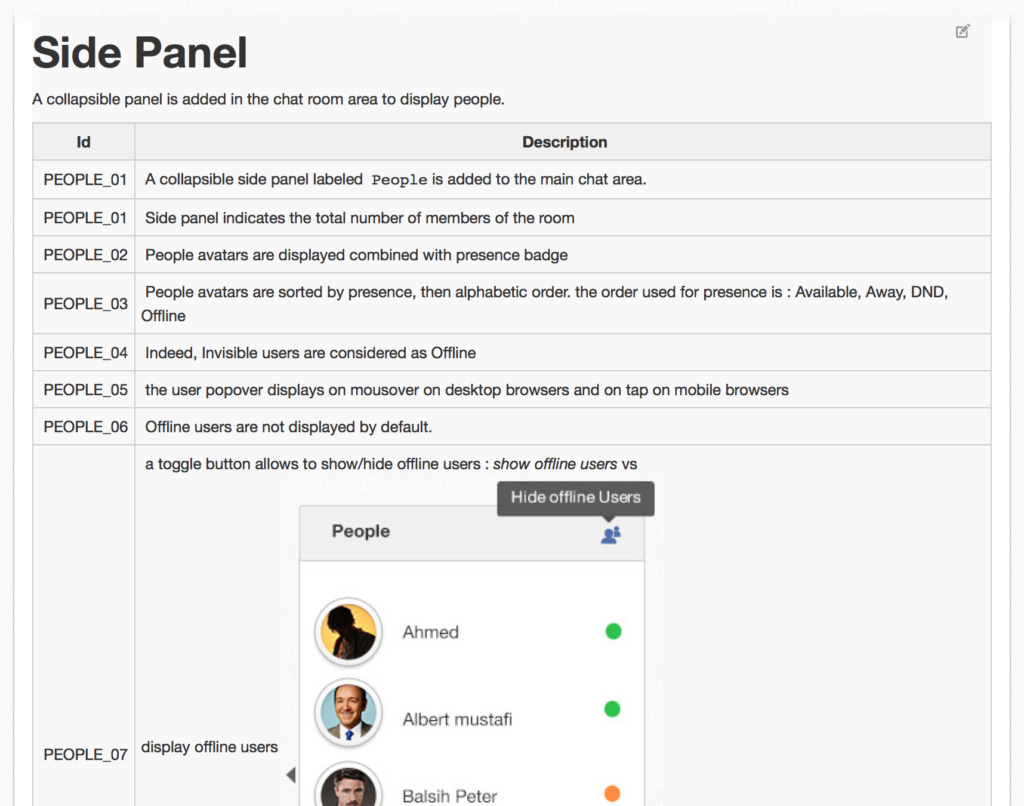

The main body of the specification is a screen-by-screen set of visual designs accompanied by a rules tables for describing interactions and the business rules that apply to them.

The rules tables contain an ID, a description, and optionally a priority and/or a target version.

As you can see, it’s nothing fancy, but it works well for us.

Using a wiki makes the specifications easy to reach for all participants, because it has a built-in full text search, and we can organize the pages in a flexible hierarchy and link specifications together. And, of course, we can edit collaboratively on wikis.

Using a screen-by-screen approach, we include many visuals in the specification. Hence, understanding the big picture of a feature only takes a quick glance. When you want to dig into it, you can refer to the table of rules below the image.

FREE WHITE PAPER

4. Writing a good specification

1: Include the designs, not wireframes

Start specifications by including low-fidelity wireframes or paper sketches. They will help you gather your ideas and provide excellent support for incepting an idea with a team. But as the design process starts, designers should produce high-fidelity visuals that developers will use to check their UI code. These designs should not just have “lorem ipsum” but actual text and labels, and you should pay attention to all details.

In particular, the state of the application captured in the design should be realistic. Include alternative states in dedicated rules if needed. Also, don’t forget to include responsive alternatives if you’re working on a mobile web app. Everything should be consistent with the rules of the specification, but also with the behavior of the other existing features. Keep updating your specification with latest designs to make sure it reflects all decisions.

2: Write concisely

Specification text can easily become boring to read. So make it less painful by writing only what’s necessary. All your words should be there for a reason. You’re not writing a novel, so try to use short, straightforward sentences with simple, expressive verbs.

Also, name things consistently along the specification. For example, don’t call that button the “Validation button” somewhere and then the “OK button” elsewhere. A bit of styling can help with that. I use a script font to refer to names or labels, and use “quoted italic” for messages I want to be implemented verbatim.

3: Add examples

FREE WHITE PAPER

Types of Digital workplace solutions

The modern workplace has evolved significantly in recent years, with advancements in technology, the growing number of tools …

4: Skip low-level interactions

There’s a common belief that a specification should be exhaustive. Well, pretty much like software without bugs is utopia, there will never be a 100% complete specification. Just admit it and avoid falling into the trap of over-specifying upfront. It’s okay to skip some low-level interaction details when you know designers and developers will work to make it look and feel smooth.

Also, many details such as validation messages, animations, and some reusable UI component behaviors are actually already captured in the frameworks your developers are using. Detailing these low-level interactions would add redundant noise. Instead, your specification should leverage a companion UI/UX Guidelines document with components and patterns that you can tap into and expand over time.

5: Iterate and call for feedback

Even if everything is clear in your mind, you will rarely write a good specification in one go. Once you’ve reached a point where you think you’ve written down all your ideas, pause and show it to other participants (your peers, developers, testers, managers, etc.). Call for feedback, and come back to it the next day. This feedback loop, along with decantation time for your brain, will almost always make you change your mind about a few things. Or it will let you find out that you forgot things. Repeat this a few times before you submit your specification to other participants for validation.

At eXo, the product managers, quality and development engineers must all agree on an informal “go” on any specification before we consider it validated and start serious implementation work. Even after being validated, a specification continues to change, because while implementing the features, developers and testers will pinpoint a multitude of special cases or functional inconsistencies that you were absolutely certain you got right!

Writing specifications requires a strange mix of rigor, creativity, and humility, but it’s a very rewarding exercise that is easy to approach, provided you put enough passion! No matter how you choose to do it, keep in mind that the best specifications are those that ease the software production process.

At eXo, all of our product specifications are publicly available, and we’d be pleased to hear your feedback on them.

company intranet

FAQs

How to Write a Good Functional Specification?

Here are some tips for writing a good functional specification:

- Include the designs, not wireframes

- Write concisely

- Add examples

- Skip low-level interactions

- Iterate and call for feedback

➝ Find some tips and tricks for writing a good functional specification

What is collaboration?

Collaboration is “the situation of two or more people working together to create or achieve the same thing”.

What are the different types of collaboration in business?

Here are some definitions of digital workplace:

- Team collaboration

- Cross-departmental and interdisciplinary collaboration

- Community collaboration

- Strategic partnerships and alliances

- Supply chain collaboration

What are the benefits of collaboration in the workplace?

Here are some of the benefits of collaboration in the workplace:

- Foster innovation and creativity

- Better problem solving

- Effectively handle times of crises

- Engage and align teams

- Increase motivation

- Attract talents

What is a digital workplace?

A digital workplace is a next generation of intranet solutions or intranet 2.0 that is based on three pillars: communication, collaboration and information. In a way this definition is true but it doesn’t cover the whole spectrum of the term. Here are some definitions of digital workplace:

- An evolution of the intranet

- A user centric digital experience

- Tags: eXo

Related posts

- All

- eXo

- Digital workplace

- Employee engagement

- Open source

- Future of work

- Internal communication

- Collaboration

- News

- intranet

- workplace

- Knowledge management

- Employee experience

- Employee productivity

- onboarding

- Employee recognition

- Change management

- Cartoon

- Digital transformation

- Infographic

- Remote work

- Industry trends

- Product News

- Thought leadership

- Tips & Tricks

- Tutorial

- Uncategorized

Leave a Reply

( Your e-mail address will not be published)