- Malek Ben Salem

- June 26, 2019

Cognitive biases in software testing and quality assurance

One of the fundamentals of software testing company as referred to by the International Software Testing Quality Board (ISTQB); is that testing helps detection of defects. Taking into consideration that humans are an integral entity in software development, it is impossible to certify a 100% bug-free programme when tests aren’t detecting any defects. Human testing detects and reduces the probability of undiscovered defects remaining in the software but even if no defects are found, it is not proof of perfection.

Aiming to minimise the risk of residual bugs in a product, many studies have been done on topics such as the tunnel effect, the butterfly effect, agile software development to name a few.

Content

However, assessing how quality and testing is compromised by human cognitive biases is an important issue that hasn’t been fully investigated.

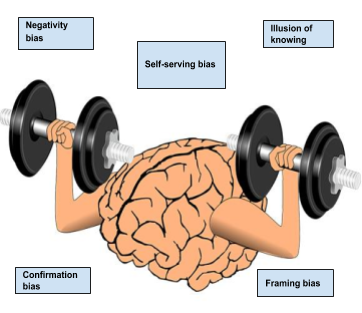

Cognitive bias

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from the norm or rationality in judgment.

It is a type of error in thinking that occurs when people are processing and interpreting information around them.

How can these biases affect the results of testing?

When starting testing, a tester is already influenced by cognitive biases through their personal judgments: which part of the product they believe contains the most bugs, who developed the functionality, the product history, etc.

It is important to know these biases in order to minimise their impact and manage them effectively.

1  Negativity bias

Negativity bias

Negativity bias is the tendency for humans to pay more attention to, or give more weight to, negative experiences over neutral or positive experiences. Even when negative experiences are inconsequential, humans tend to focus on the negative.

For example, testers will not easily sign off for release when there was undetected bug in previous versions or projects. They still want to perform more tests to overcome this failure.

In order to reduce the effect of this bias, it is always better to analyse each project/version in terms of risk and define objectives before starting the tests.

The pairing of objective and risk allows defining the measurable exit criteria (to determine if the product is ready to be released) in which the tester gives his release agreement.

2  Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms the tester’s previously existing beliefs or biases.

In general, if we think that the code of a specific developer has more defects than the code developed by others, then we will believe that we should spend a lot of time testing that module.

However, being under the influence of these beliefs will tend to increase the risk of not detecting defects in modules developed by other developers.

To reduce the effect of this bias, it is advisable to review the test booklets, test plans, test suites by other team members before starting the tests.

3  Framing bias

Framing bias

Framing bias occurs when people make a decision based on the way the information is presented, rather than on the facts.

The same facts presented in two different ways can lead to people making different decisions.

For example, the decision whether to perform a surgical operation may be affected by whether the operation is described in terms of success rate or failure rate, even if the two figures provide the same information.

In other words, testers tend to validate only expected behaviour, therefore, negative tests are ignored. So, when writing test cases, we tend to cover all requirements with their expected behaviours and to miss out on negative flows as not all negative flows are specifically mentioned in the requirements.

4  Self-serving bias

Self-serving bias

This bias is the tendency to perceive oneself in an overly favourable manner. It is the belief that individuals tend to ascribe success to their own abilities and efforts, but ascribe failure to external factors (“the environment provided does not work”, “it works properly on my PC”, etc.)

This attitude has the effect of turning one’s back on continuous improvement, which is one success keys of testers.

In order to reduce the effect of this bias, we must apply the Japanese concept of continuous improvement, named ‘KAIZEN’ that prompts the question: What I could have done differently to minimise or solve this problem on my side?

5  Illusion of knowing

Illusion of knowing

The illusion of knowing is the belief that comprehension has been attained when, in fact, comprehension has failed. For example, the situation is wrongly judged to be similar to other known situations, so the person reacts in the usual way without trying to gather other information. Thus, the tester can under-exploit other possibilities to test the system or create new test cases.

This bias guides our perception and limits our ability to think outside of the box get out of the box, resulting in missed bugs.To reduce the effect of this bias, it is better to ask questions in case of doubt and validate the specifications as soon as the first drafts are available.

Conclusion

During the post-project analysis phase, we analyse the statistics and the deliverables (documents, reports, KPIs, software, etc.) and we tend to neglect the psychological effects of the success or failure of a project.

Sometimes, the cognitive side can be the main reason for the success or failure of a project. This blog has shown the potential impact of certain cognitive biases on software testing activity.

eXo Platform 6 Free Datasheet

Download the eXo Platform 6 Datasheet and

discover all the features and benefits

discover all the features and benefits

- Tags: eXo, Future of work, Industry trends, Tips & Tricks

Rate this post

Being a Quality Assurance manager at eXo Platform, I am mainly responslible for defining and implementing quality strategies all through the product lifecycle. Focusing on our "Customer Centric" approach, we ensure the product compliance with internal and external requirements.

Articles associés

- All

- eXo

- Digital workplace

- Employee engagement

- Open source

- Future of work

- Internal communication

- Collaboration

- News

- intranet

- workplace

- Knowledge management

- Employee experience

- Employee productivity

- onboarding

- Employee recognition

- Change management

- Cartoon

- Digital transformation

- Infographic

- Remote work

- Industry trends

- Product News

- Thought leadership

- Tips & Tricks

- Tutorial

- Uncategorized

Laisser une réponse

( Votre adresse email ne sera pas publiée)

Connexion

0 Comments

Commentaires en ligne

Afficher tous les commentaires